Tips for Teaching the 2024 Presidential Election, Part Two: In the Classroom

#1: Make a community agreement (posted 1/29/24)

For anyone who has seen me present, this is old news. But for everyone else, I urge you to craft a set of durable, visible, thought-provoking norms that will help students understand how they are supposed to engage with each other. The election might get slippery. Communities need guardrails. These are the guardrails.

Many teachers have some version of such an agreement, although they tend to get neglected (see: dusty, faded poster you once triumphantly laminated but which you now only notice when the thumb tacks get knocked off). It’s time to get back to that agreement, to revise it if necessary, or to craft a new one. Facing History has a helpful lesson on co-creating such an agreement (which they call “contracting”) with students.

For my money, a useful community agreement (or contract, or set of norms, or whatever you want to call it) will probably include two sort of different, but complementary, sets of commitments. One is about behavior, such as, “We agree to…

Listen to learn, rather than to refute

Avoid interrupting

Ask follow-up questions

The other set of commitments is more about mindset—it’s about cultivating a way of thinking that will in turn drive classroom behavior. This could include statements such as, “We agree…”

that listening does not necessarily indicate endorsing or agreeing

that we are enhanced, rather than diminished, by being around ideas with which we disagree (with thanks to Simon Greer, whose Bridging the Gap initiative is now managed by Interfaith America)

to take winning off the table (with thanks to the Better Arguments Project for that language)

Those are meaty statements, and not all teachers may agree with them. Think carefully about what you are trying to teach, though, and be sure that the rules of your road—in a classroom or the broader learning community—guide students toward the goals you value. Get your agreement in order, and then feature it relentlessly. If you make it matter—if students see that you mean what you say—it will provide the stability and clarity you’ll need when the divisiveness of the election starts to feel oppressive.

#2: Look for the helpers (posted 2/1/24)

Our political leaders can be terrible role models (some, yes, are really, especially terrible). It is therefore understandable that teachers might hesitate to attend to the election because doing so—featuring this nasty rhetoric—feels like more of a disservice than a service to our students.

But we can show our students examples of elected officials who are in fact playing nicely. The joint campaign ad of the 2020 Democratic and Republican candidates for governor of Utah is one example. Spencer Cox won that election and, as the current Chair of the National Governors Association, has launched a Disagree Better initiative that features video snippets of governors of opposing political viewpoints engaging in civil discourse.

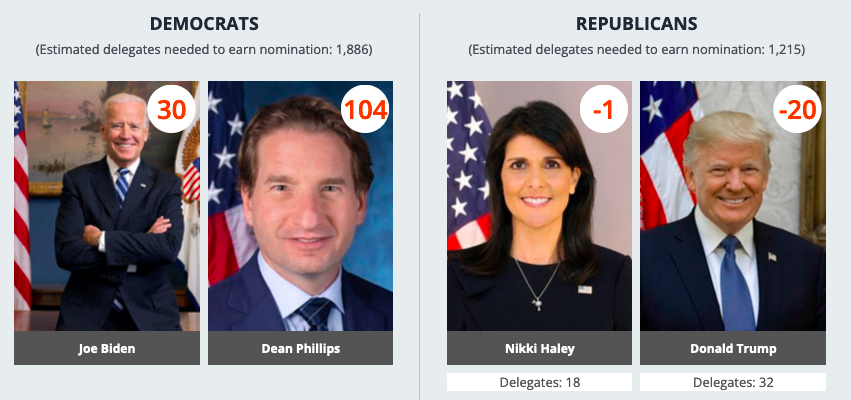

Another resource with potential is the Common Ground Scorecard, which rates officials on their commitment to working across lines of disagreement to solve problems. On a scale of 1 to 100 (with the tantalizing possibility of losing or gaining up to an extra 20 points due to extraordinary behavior):

President Biden has earned a 30.

Former President Trump: -20.

Dean Phillips, who is likely to have completely disappeared from the electoral radar (if he was ever on it) by the time you read this, has earned a 104. 104!

The election will naturally pull our attention toward the usual suspects. But if we are interested in helping kids learn how to work across lines of divide and disagreement, let’s use the energy of the election to also drive students towards the models we wish them to emulate (there are many on the Common Ground website). I’ve often heard people ask, “Where are the examples of politicians actually working and speaking across the aisle with civility?” They are out there. Let’s help our students discover them.

#3: Go local (posted February 5, 2024)

Just as we can leverage the buzz of the presidential election to highlight leaders who bridge divides, we can also turn our attention to those overlooked “down-ballot” candidates—the folks running for a congressional seat, or mayor, or even school board or city council positions.

We can capture many of the same learning opportunities this way—we can look at maps, and do math, and discuss campaign promises. But, in contrast to the presidential candidates, we can get a lot closer to the people who in most cases are going to be much closer themselves to the issues that affect students’ lives on a day-to-day basis; and we can probably get some of these folks into our schools to actually talk with our kids.

The presidential election will function like a black hole – scary, awesome, with an unimaginable gravitational force. And black holes are so interesting! I’m not one to turn away. But the presidential election could also sort of be like a portal that draws our students and then, when we’ve got them interested, allows us to take them somewhere else-- like the local elections.

#4: Strengthen media literacy skills (posted February 12, 2024)

We all see it coming: a well-intentioned teacher uses an article, or video, or snippet of a podcast to feature some development in the election that connects nicely to class. The next day, she receives an irate email from a parent who simply cannot abide this bias and who reminds the teacher that schools are meant to teach students how to think, not what to think. Shaken, the teacher ends up in the office of her supervisor, who listens sympathetically but suggests that in the interest of balance, she try to give equal weight to news sources from the right and left. Reasonable enough, yes?

Sort of. But let’s remember that the consumption of media—media of all sorts and all biases—provides ideal fodder for the development of critical-thinking skills. Instead of avoiding media that could be construed as “biased” (because it’s all biased), or even mechanically inserting a second source of news to “balance” another, let’s make it simpler for ourselves and much more powerful for students: let’s ask them to critique all the media—whether we provide it or they find it on their own.

Maybe you find a thought-provoking article in the New York Times about how gun-control is being discussed on the campaign trail, and—what timing!—you were about to study the Second Amendment. Great! Use that article! And while using it, to help build the habit of critical inquiry, have students analyze the article, perhaps using this guide from the Media Education Lab:

Maybe a Fox News video raises concerns about President Biden’s age. And you’re thinking to yourself, Huh, if this weren’t Fox News, it would actually be interesting to watch this together since we’re about to discuss the requirements to be president. But I don’t dare use Fox News in class, do I? Sure, you dare, because, as with any piece of media we incorporate into our teaching, we can do two things simultaneously: address the relevant content (in this case the constitutionally-stipulated requirements to serving as president) and also teach kids to think critically by having them analyze the media we’ve featured.

Does it make sense generally to expose students to a wide array of media from across the political spectrum? Sure. Of course. But are we serving them by almost robotically inserting a left-of-center media outlet alongside a right-of-center piece just for form’s sake? Let’s let the analysis of media be the tool that helps sharpen students’ critical thinking skills, rather than sanitizing their media stream by curating out the possibility of imbalance. Let’s let the students conclude on their own, through rigorous analysis, that a given piece of media has limitations, rather than assuming we have to do it for them.