Open letter of response to Turning Point USA’s podcast

Sent October 7, 2025:

I lean left politically, and in responding to your October 1 podcast, I’m trying to do the work I ask of students and teachers —which is to connect respectfully with those across the political divide (please feel free to kick my tires here). You said you read all incoming email, so here’s hoping this one is worth your time!

First, I am deeply sorry for your loss. It struck me, listening to the podcast, that you bring a high degree of clarity, purpose, and energy to your work, and it must be enormously challenging to maintain that professionalism as you simultaneously mourn a personal tragedy. My thoughts are with your team as you face both challenges.

My intent in this email is not to refute the content of the podcast. Instead, I’d like to do two things: 1) reflect back to you areas of agreement, even across the political divide and 2) hit you with areas of concern that exist on my side of the divide and that I hear echoed in your own concerns. In other words, I’m trying to build bridges.

To my ear, one thread of your podcast was a longing and advocacy for genuine personal connection. I heard talk of babies and how children naturally drive parents toward community as they build a network in support of their kids. As a longtime educator and father of two, I found myself nodding along. Sometimes those connections eventually prove to have been superficial and situational, melting away after the birthday parties have passed, while others endure. I fret constantly about my teenage kids’ isolation—physical isolation imposed by the pandemic, followed by alienation bred of the digital onslaught—and I, like you, want desperately for all of us (but especially my own kids) to enjoy the fruits of meaningful human connection. I think I heard in the podcast an assertion that conservatives are generally more connected than progressives, which is something that had never occurred to me. Is it true, I wonder? I’d be curious to hear more.

I was struck by the feeling of threat expressed in the podcast. Your guest mentioned many frightening incidents (slashed tires, SWAT episodes, etc.), and you also talked about enduring a culture of low-grade violence and intimidation, such as when college students ransacked a Turning Point table. I get this—there are steps that precede or lay the groundwork for more overtly violent acts, and we ignore those intermediate acts of aggression and intolerance at our own collective peril. It would be eye-opening, I think, for many of my progressive friends to hear of your experiences.

And this is where I gently ask you to hear that my shared concern comes from a different perspective. That very same unease about an unchecked culture of intimidation, a casual encouragement of violence, is one of the reasons I worry about President Trump. What some may hear as bold, frank presidential talk—to be celebrated, if that’s the way it is received—often sounds to me as demeaning, intolerant, and supportive of violence. This is not to refute what you have said. I do not for a second doubt the threats you experience. It just strikes me that your experience living with this threat positions you to understand that many of us across the political divide share that same dread, amplified by the powers at the president’s disposal.

It sounded to me as if you feel genuinely besieged—not only by the personal experiences I already mentioned, but also by a wider threat coming from the left. You cited a Rutgers study that alarmingly revealed robust support for political violence among those on the far political left. I tracked down that study, read it, and found it credible. In fact, when I present to teachers, as I often do, I intend to incorporate some of the study’s findings to make educators aware of what the authors call an “assassination culture” that may be fueled by online ecospheres. I can understand why you feel besieged, and it would be eye-opening for those in my progressive orbit to learn about this reported far-left support for political violence (We all tend to occupy our own, affirming news ecosystems, and it does not escape me that I had never seen the Rutgers study; I had to listen to a podcast run by folks across the political aisle to discover it).

Even as I acknowledge the disturbing findings of that report, I also lift up a research summary from More in Common that highlights two important findings: that overall support for political violence, as measured by an array of studies, remains very low in this country, yet many of us vastly overestimate the extent to which people across the political divide support such violence. This perception of danger from beyond can have the effect of heightening our defensive instincts—of sharpening our knives in anticipation of attack.

And many things can be true at once. It is true that you have experienced intimidation, that your guest has experienced personal targeting and attacks, and in fact that the leader of your organization was murdered. The Rutgers study shows us alarming support for political violence among a segment of what the authors call the “extreme left,” and I can’t imagine many would doubt the threat emanating from quarters of what we could call the “extreme right.” Still, it can be—and is—also true that our collective perception of threat does not match reality. And where there is genuine threat, I would hope we could move past a binary view of it. Your guest pointed out that conservatives generally should not be lumped together with “some KKK member.” We should be able to agree on that and that the left, broadly, is not represented by a subset of those who would support violence.

And yet there is a persistent drumbeat of rhetoric in this country that attempts to reduce our complex relationships to simple matters of good versus evil, us versus them. I respect your work, I admire your perseverance in the face of overwhelming tragedy, and I mourn your loss. But when I hear on this podcast a recurring reference to the bifurcation of morality in this country—which to me means a belief that conservatives follow a moral compass, while liberals do not—and with it a repetition of the threat that comes from that amoral half of the country, I connect that messaging directly to similar framing by the president as well as policy decisions intended to combat that threat, such as directing the military to fight the “threat from within.” This worries me.

What I am trying to convey, and what I hope you hear is this: that I agree with you on important matters, that I can learn from you—that I have learned from you—and that I also have insight to offer. I hear your worry about safety, and I understand it, even as I ask you to resist painting with a broad brush the entirety of the left-leaning electorate as a threat, because doing so fuels a culture of distrust and a fear of attack that can, in turn, spark preemptive aggression.

Here's my hope: that you’ve read this and considered it carefully, believing that it comes from a place of well-intentioned constructive engagement in the spirit, as I understand his legacy, of Charlie Kirk. Beyond that, if I could cash in a genie-granted wish, it would be that you might share some of my thoughts with your listeners. And if we were really going for broke, I would hold out a glimmer of hope that this would be our first, rather than final, exchange—that we could, in some way, sustain the conversation. We are fellow Americans, in this together, trying to make this world the best it can be for our children. Let’s keep talking.

Best,

Kent Lenci

Founder

Middle Ground School Solutions

Good news! Colleges increasingly emphasize engaging across the political divide

This week, the news of American division and disfunction feels particularly dire. We are all in need of some hope. So here’s some: colleges and universities are working overtime to provide students with experiences and training to help them reach across the political divide. From where I sit, it appears that over the last year or two there has been an explosion in the number of programs, classes, and offices dedicated specifically to helping young Americans talk to and work with people with whom they disagree.

Examples abound. At Stanford, first-year students are required to take Citizenship in the 21st Century, a course that provides “the setting and skills to engage in rigorous, intellectual discussions on topics that that can be contentious—controversial, even.” At UC Berkeley, a course called Openness to Opposing Views helps students learn “how and why to engage with viewpoints they don’t understand. In 2024 Vanderbilt University required incoming students to read Monika Guzman’s book, I Never Thought of It That Way, before she spoke on campus about engaging in civil discourse.

Dartmouth College’s Dialogue Project

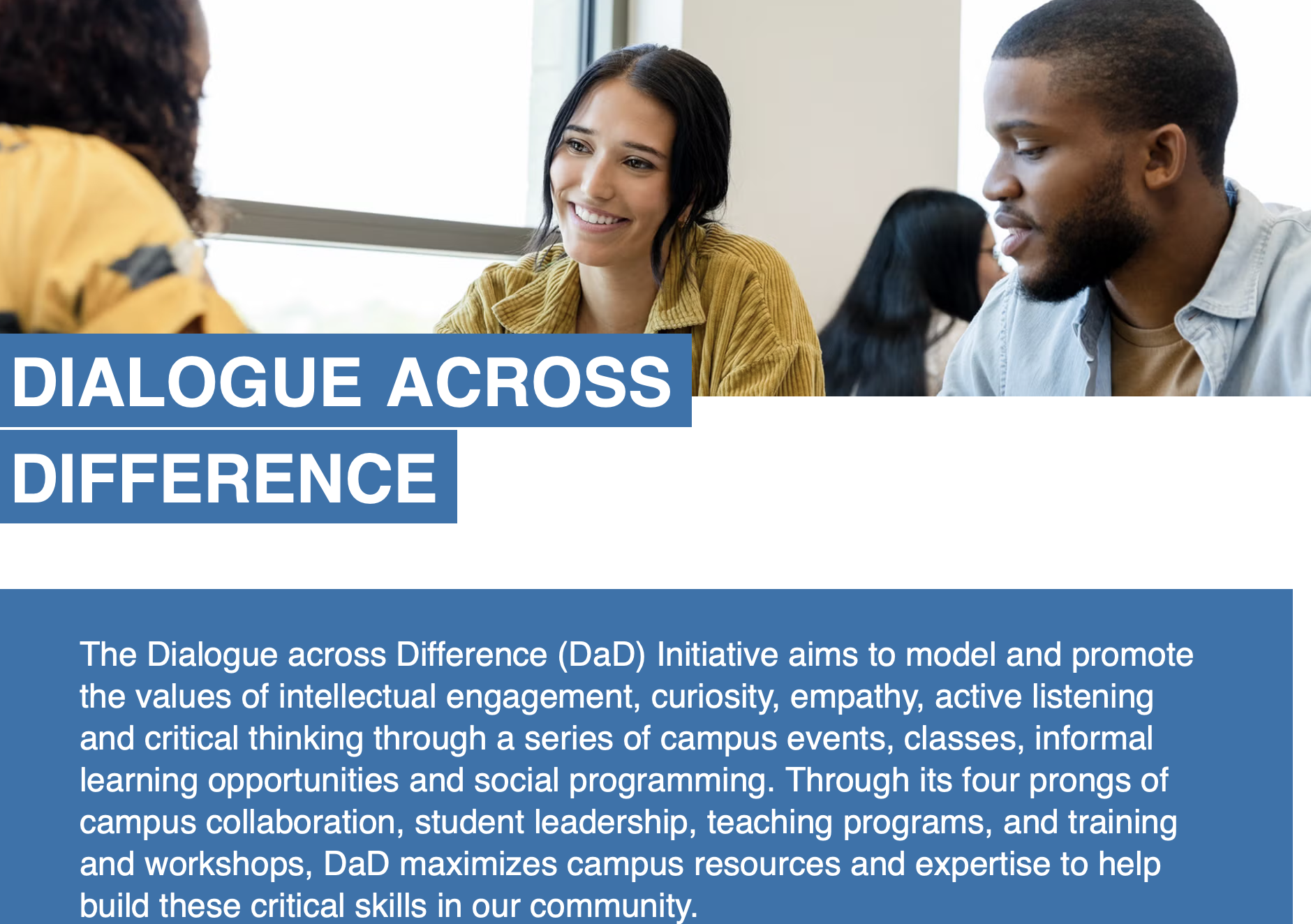

At American University, The Project on Civil Dialogue envisions “a campus driven by intellectual curiosity and good conversations.” Dartmouth College’s Dialogue Project helps students and faculty build the skills that anchor productive discourse across lines of disagreement. In addition to workshops and speakers, the project brings StoryCorps’ One Small Step initiative—in which two people across the political divide engage in a recorded conversation—to campus. William and Mary is leaning on the Better Arguments Project to guide community behavior. UCLA has a launched a Dialogue across Difference initiative. As the Chronicle of Higher Education observed in August, dialogue is in.

UCLA’s Dialogue across Difference Initiative

This is good news for today’s college students, and I hope it will be good news for today’s K-12 students, as well. I am ever so hopeful that this flurry of dialogic opportunities portends a longer-term emphasis on teaching college students to reach across lines of divide and difference. If so, there is likely to be downward pressure on schools to send colleges kids who’ve already had a head start. For several years I have been preaching the need to equip today’s students with the skills they’ll need to ease tomorrow’s political polarization. I think in colleges and universities I may have found some new voices to join me at the pulpit.

Teachers should be sharing their politics with each other. Here how and why.

I recently heard of a parent who, envisioning the year ahead, said her one hope was that her child would learn to talk to people with whom she disagreed. I have a hunch she’s not alone. Political polarization feels ever more acute, and divisions fueled by disagreement over incendiary issues such as the Hamas attack and subsequent retaliation by Israel have left gaping wounds in many school communities.

Parents have good reason to hope their children will learn to speak civilly and productively with those across the divide, and educators want this for their students. It is my strong belief, though, that to deliver these skill sets, we adults need to sharpen them ourselves. Teachers must become the bridge-building models their students will emulate.

Research confirms what simple intuition would suggest: that we need to get to know the people with whom we disagree. Studies find personal stories to be more persuasive than facts, and researchers behind the Strengthening Democracy Challenge found that political animosity is eased by exposing people to the stories of likeable folks from across the aisle. The strategy works in the lab, and it works in real life.

I know, because I have led teachers through the practice of sharing stories across the political divide. In my final year at Brookwood School in Massachusetts, I was fortunate enough to partner with teachers who were willing to gather and listen carefully to the narratives of their colleagues. You might call these “political origin stories”—tales of forming worldviews—about which attendees could then ask follow-up questions and reflect back what they had heard (for more, see chapter 7 of my book, Learning to Depolarize).

Those who shared stories felt rejuvenated and buoyed by the experience, while many of those who listened found themselves similarly refreshed. “Listening became a gift,” said one attendee of the gatherings. “Colleagues left the space excited and invigorated by our exchanges,” said another. The feedback was overwhelmingly positive.

This past school year, I joined the Civi Coalition, a network of educators in western New York, to lead a similar activity. During the second half-hour of monthly, virtual meetings, attendees could choose to join the “bridging” breakout room, featuring an educator sharing their political origin stories—stories of family members, and lessons learned in college, and the pressure to conform to the expectations of a political tribe. As had been the case with our gatherings at Brookwood, those who shared felt validated and unburdened, while those who listened came to understand and respect those with whom they might have disagreed.

This model—of educators gathering in person or virtually to share with each other the origins of their political beliefs—is easily replicable, if unusual. It’s not hard to imagine the questions: Is it even professional development? Where is the pedagogical expert and the takeaway to implement Monday morning? Is it even appropriate to talk about politics? If so, what’s the point? Indeed, what I describe is unorthodox, but I would suggest that no one who observes our national condition could say that we educators are producing citizens who are equipped to reach across lines of disagreement to solve our seemingly intractable challenges. That work starts with us.

If it does, the experience should adhere to a handful of principles: First, it should be voluntary. For a host of reasons, little good—and possibly a furious backlash-- will come from forcing unwilling participants into an experience such as this. On the other hand, providing the opportunity for those who choose it is likely to spread seeds of growth beyond the initial cohort. Secondly, it should be designed and marketed as primarily a listening exercise, rather than a “conversation.” We don’t need more opportunities to engage in unproductive back-and-forths across the political divide, but we do need to discover the humanity in those with whom we disagree. We also need to practice the habits—such as listening—that we value in our students.

Thirdly, the experience should be tightly structured to ensure the emphasis on listening, with a time limit imposed for the sharing of stories and with each step of the process laid out in advance and faithfully implemented by the moderator. Those steps should include a time for follow-up questions and a separate period to reflect back what attendees have learned. Affirmation comes from being met with questions of genuine curiosity as well as meaningful responses to the sharing of one’s story, and affirmation, in contract to contempt, is a critical ingredient in softening lines of divide.

The cohort could be within a school, as it was at Brookwood, or it could connect teachers within some broader network, such as the Civi Coalition in New York. A prerequisite is some degree of political heterogeneity, and schools that find themselves loaded with teachers of one political stripe may be good candidates for the latter approach (although I would also suggest that the faculties at most schools are more politically diverse than they might appear; even a very small number of teachers in the political minority are enough—if they are willing participants—to help launch this sort of initiative).

What could come of it? A proper study might help us determine if we were effecting the outcomes we sought: to increase the appetite among teachers to engage across the political divide and, consequently, wider and more purposeful implementation of measures to help students develop their own bridging tendencies. Until such a study materializes, we’ll have to follow our instincts. Experience tells me that providing a cross-cutting forum for teachers to share personal stories has the effect of bridging the political divide. It seems likely to me that, armed with this experience, those teachers will be more likely to help their students discover similar opportunities. At that point, we might just begin to meet the need, expressed by that parent I recently heard of, to teach kids how to talk with those with whom they disagree.

Media literacy has become controversial. Here’s how to handle that.

A new year! Maybe some new carpet in your classroom? Certainly some new students! Things are looking rosy, even if the world beyond the classroom walls feels somewhat treacherous. Perhaps, you’re thinking, the peril of current events can be assuaged by the promise of media literacy; let’s teach these kids discernment, so that they use media rather than allowing it to use them.

By all means, let’s commit wholeheartedly to teaching media literacy, but let’s also face the fact that many, many people are deeply suspicious of it (read more about this here). In my experience, much of the opposition views media literacy as illiberal and censorious. As prominent legal scholar Jonathan Turley has written, “A new industry of ‘disinformation’ experts has commoditized censorship, making millions in the targeting and silencing of others.”

So please, know this: where I might view media literacy as a vital skill that will help students navigate news with a critical eye, there’s a very good chance that some parents of your students understand the term as a call to arms in a war against minority viewpoints (if this seems illogical, take a peek at my longer piece for a more thorough explanation).

As with other contentious subject matter, we have a handful of choices about how to handle it: we can skip it entirely, we can carry on as usual, or we can stick with our curriculum but anticipate opposition and proactively engage the skeptics. I would suggest that the latter choice is the one that stands a chance of mending, rather than further fracturing, the partisan divide that underpins the opposition to media literacy.

So what would that engagement look like? For me, it looks like a bit of extra work now that will probably save a bunch of time, aggravation, and labor later in the year. This might start with communication—via a weekly class email, or in a presentation at back-to-school night, for example-- in which you invite parents to share their hopes and dreams by asking a question such as, “How do you hope your child uses media in the coming years?” Or, “What worries do you have about your child’s access to media?”

The responses will share common themes: that parents want their kids to develop healthy habits, that they want them to be happy, that they want them to think for themselves. If it were me, I would reflect those themes back to the parental audience by saying, “It sounds like many parents are hoping….” This is the cue to then share your plans and how those plans will help realize our shared objectives.

I’d start with where you draw your inspiration—what grounds you—in your big-picture understanding of media literacy. So, for example, maybe you tell parents that your approach to media literacy education begins with the vision of the National Association for Media Literacy Education, or the five key questions of the Media Education Lab. It’s important to have a compass that guides your journey and to share that grounding with parents.

Then, I would give a taste of what students will actually experience in the classroom. For example, if news is a part of the curriculum, I would share with parents that their kids will access sources that strive for balance and/or explicitly offer perspectives that span the political spectrum, such as Tangle, AllSides, or Ground News. If you share my belief that learning to recognize and navigate bias requires exposure to bias, you could also tell parents their children will sometimes access news-- NPR or the opinion page of the Wall Street Journal, for example—that is considered by some to have a slant. Parents would be interested to hear about resources such as the media bias chart from Ad Fontes that can help students analyze news outlets’ bias and reliability.

We all know political polarization is a challenge. Many of us respond to that challenge by trying to stay apolitical. This will not work. If we were to actually “avoid politics,” we’d be left with little of substance to teach. So, although media literacy is among the many subjects that stir the political passions, it’s important stuff. Let’s teach it. But let’s also be realistic in anticipating that some folks will reflexively mistrust this teaching unless we get ahead of the conversation. Don’t wait to be ambushed later in the year. Engage parents now to build a common understanding of the goals of this teaching so that our students can develop the skills they’ll need to wisely and purposefully navigate media and society.

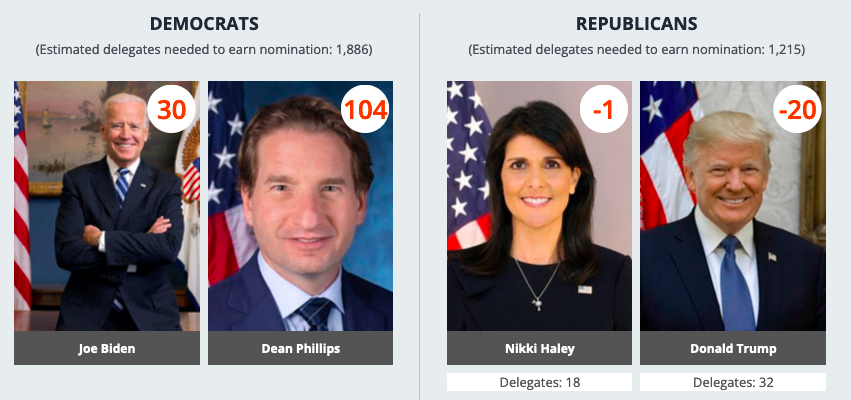

I sent 30,000 emails. Was it worth it?

Along with other volunteers, I spent a week emailing across the political divide. Here’s the exchange that one of those 30,000 emails yielded.

A couple of weeks ago, I joined a dozen or so other volunteers to launch a massive email campaign helping researchers execute their plan to “use research-backed techniques to help Americans communicate across the partisan divide.” As one might expect, most of my emails were ignored. Some were met with guarded interest:

Others with hostility:

(yes, that appears to be a barf emoji)

In all cases, I replied. Alas, only one out of those 30,000 emails led to a proper back-and-forth. And even that exchange did not come easily, with the initial response to my message falling well short of cordial. In my outgoing email, I had done what the researchers said to do: express curiosity about those across the political aisle and share a story that would illustrate where I was coming from. That story was a brief observation about how the New England waters in and on which I have spent my life have warmed, changing the weather we experience. That, my new pen pal said, was nothing but “media upchuck,” before quoting back to me part of what I had written and then trying to correct me:

I had a physical reaction to that response. My muscles tensed. My heart rate increased. I could literally feel throughout my body my indignation at having someone tell me that my own, first-hand observations were… what? fabricated? the product of media-induced brainwashing? It was hard to stomach this response, and I know that many of my fellow Americans have been in this very spot. We are outraged by something we hear or read or see. Red alarms flash. We know it is not worth going there, so we do not.

Eschewing common sense, though, I leaned into the challenge for which I had volunteered. When I could think clearly (which was several hours later), I did my very best to respond with humility, curiosity, and what I hoped came across as a friendly tone:

This time, my correspondent actually signed her name, with a phone number listed beneath. This seemed like a positive development. She also rewarded me with a link to an animated YouTube video in which one cartoon character disabuses the other of its concern over climate change. The voices were computer generated. The dialogue was highly intellectual; it sounded smart. And yet, there was no author or creator listed, no citation of particular studies that could be searched or verified, no transparency at all. I could see how someone—especially someone predisposed to doubt climate change—could find it convincing. I tried to stay in the conversational game:

I did not get answers to my questions, but I also didn’t lose her:

(pretty sure she meant “elected officials” have failed us, rather than the “electorate” who choose them)

It would turn out that our conversation had pretty much run its course. I responded, leaning into the opportunity to find some common ground, but my message ended up closing our exchange. I didn’t hear back again.

So, did the researchers learn anything? I sure hope so, and I’ll await news. Did I learn anything? I think so. I confirmed that, even in the face of what seems like a nearly insurmountable gulf marking the political divide, it is possible to soften the tone, to conduct a cordial exchange, and, I suspect, ease the feelings of threat one may feel coming from the other side. 30,000 emails, and just one (pretty darn difficult) exchange to show for it. Was it worth it? Yes, I think it was.

How I would teach President Trump

At the end of the year, another parent would thank me and say, “I wish I had learned all this when I was in seventh grade!” And I would think: It’s not too late! It’s not too late for you to get curious about the freedom of press, and the function of executive orders, and the balance of powers, and the biases of media sources. It’s never too late to dig deeply, to learn joyfully, and to be curious about those with whom you disagree. A seventh grader can do it. So can you.

I think often about how my students would learn from President Trump if I still taught middle school. How would I teach American government, when every move felt so fraught with danger? What would I do?

I’d teach civics. I’d take the firehose of news, spray it around the room, and we’d all soak ourselves in civics. President Trump would criticize a judge, and we’d talk about the federal court system—what an appeal is, and what judicial review is, and what the Supreme Court does. This would lead us to a discussion of checks and balances. My students would pepper me with questions, some of which I could answer directly (“Wait, so could Trump fire the judge?”) and some of which I could not; those would be the best ones. “Is the president more powerful than the other branches? What would happen if the president decided not to do what a judge told him? Why is lunch so short?”

Mr. Trump would hint at a third term, and a student would say he can’t do that. “How do you know?” I would ask, and we’d all dig into our little pocket constitutions. The nature of executive orders would puzzle kids, but those orders would help us see that the president runs the executive branch of government and can dictate the direction of its work. And because everyone would then get confused about what a law is, as opposed to an executive order, we’d be all set up to learn what Congress does.

I would use President Trump to teach media literacy. Students would bring in news headlines and week by week we’d paper over a bulletin board, analyzing the headlines’ language and inferring the point of view of the editor or author. “This one loves Trump!” a student would say. And that would make us check the text of the article to see whether a close reading supported that claim. This focus on news would drive us back to the First Amendment. I’d shout, “You can’t HANDLE the press!” and not a single kid would know I was misquoting an old movie. They’d roll their eyes at me.

I’d also use President Trump to teach habits. Before we puzzled over executive orders or freedom of the press, we would make rules for ourselves: that throughout the year, we would strive to ask questions rather than refute what others said, that when possible we would turn our bodies toward speakers and reflect back what we had heard in order to validate and clarify. We’d learn to identify and regulate emotions when classmates said things that set us off. We would return to these—and other— expectations throughout our discussions, collaboratively nurturing a culture of curiosity, even about those with whom we disagree. If elected officials—including President Trump—publicly disregarded the norms we had agreed to follow in our learning community, the contrast would sharpen our focus.

I would be questioned along the way. A parent would email, saying that the widespread condemnation of President Trump among my students was marginalizing her conservative son. On the very same day, another parent would ask how a class devoted to civic education could platform an authoritarian figure like Mr. Trump. If I were feeling overwhelmed and cornered, I would reply hastily and defensively; I would not hear from either parent again. If I took a deep breath, I might invite each parent to join me for a more thorough discussion. I would either end the conversation before it began, or I would practice the very behaviors I was hoping to teach my students.

At the end of the year, another parent would thank me and say, “I wish I had learned all this when I was in seventh grade!” And I would think: It’s not too late! It’s not too late for you to get curious about the freedom of press, and the function of executive orders, and the balance of powers, and the biases of media sources. It’s never too late to dig deeply, to learn joyfully, and to be curious about those with whom you disagree. A seventh grader can do it. So can you.

The Trump Conundrum 2.0

Is it possible to maintain impartiality while also critiquing aspects of the President’s rhetoric or actions? It’s a vexing question, one that I and many other educators have faced, and one that I continue to consider as a member of the bridging community.

For almost a decade, I have wondered whether it is my place to critique Donald Trump. This isn’t my first time writing about it.

When I taught middle school, the risk lay in eroding my standing as an impartial authority and inadvertently giving students a political nudge. Now, as I devote myself full-time to bridging political differences, commenting on Trump risks alienating those in support of him and exacerbating the divide I work daily to heal. My professional focus is on equipping today’s students with the skills and mindsets to ease tomorrow’s political divide. I am deeply involved with what is known as the “bridging” movement to help mend the fraying fabric of American society across lines of political divide. So I really don’t want to make this divide any worse than it already is.

And yet, it feels awfully important to comment on President Trump. I find his comportment, character, and mean-spirited rhetoric loathsome. His disdain for the rule of law and for the constitution render him, in my view, unfit to serve as president. These truths are worth surfacing in a school, where it is the duty of educators to encourage moral clarity and civic fluency, and they are worth surfacing in our democratic society more broadly. We do not consider it an open question as to whether we support laws, coequal governance, and civil liberties. It is in the common interest to call out an attack against these principles.

It has also felt important to me—when I taught and now, as I build bridges across the political divide—not to comment on Trump. I try not to editorialize on Trump’s policy proposals (including, of course, the many with which I vehemently disagree). I also painstakingly avoid the simplistic trap of opposing the “MAGA movement” or any other label that would include those in the Trump camp. My critique of President Trump does not extend to those who support him.

When Trump first found the political limelight, his appeal eluded me. I am much better these days at empathizing with those who support Trump, though, and I understand that they do so for an array of compelling reasons: our immigration system was broken; it felt hazardous to be a person of faith; globalism had stolen our jobs… and a hundred others. These are my neighbors, my family, my friends, my colleagues, and my fellow Americans. I can be concerned over Trump’s rhetoric and his corrosive effect on our democracy yet simultaneously acknowledge that his support comes from a place of good faith.

Indeed, I can even understand that the issue that is of most concern to me—Trump’s antidemocratic tendencies—is itself contestable. I am shaken by Trump’s attacks against judges and law firms, his blanket pardon of January 6 insurrectionists, his dismissal of the constitution, and his recent promise that he “isn’t joking” about running for a third term. And yet, lots of people support Trump for the very reason I find his actions disqualifying; they cherish the rule of law. They might decry Democrats’ attacks against judges, or understandably condemn the shady origins of the Steele Dossier that set Trump on the road to impeachment. They see in President Trump a man who is willing to stand up to this betrayal of the democratic process.

So it’s a bit of a tricky business, this question of whether one can maintain credibility as a teacher and as a bridge-builder while commenting on President Trump. In each role, one aspires to be trustworthy, fair, and openminded. Does taking a stand on certain aspects of Trump’s governance, even while reserving judgment on most of the political platform on which he stands, undermine the trust of those who focus on Trump’s merits or the promise of his actions?

I’m not the only one thinking about this. Zachary Elwood argued in a recent essay in The Hill that one could do so and still ease toxic polarization. Heidi and Guy Burgess cited Elwood’s piece and added their own thoughts in their March Substack post. The American Bar Association has landed on the side of public condemnation, issuing a series of statements criticizing President Trump’s recent actions. “We reject efforts to undermine the courts and the profession,” wrote the ABA President on March 26. “We will not stay silent in the face of efforts to remake the legal profession into something that rewards those who agree with the government and punishes those who do not.”

Was this the right move? If ever there were a group of professionals trained to see both sides of things, it would have to be lawyers, some of whom have defended Trump with every ounce of their professional abilities while simultaneously disdaining him as a politician. Nonetheless, they appear to feel that Trump has crossed a line. In an earlier statement, the ABA President wrote, “The American Bar Association has chosen to stand and speak…. We invite you to stand with us.”

Braver Angels, whose mission is “Bringing Americans together to bridge the partisan divide and strengthen our democratic republic,” has taken a different approach. In a recent email to members, National Ambassador, John Wood, Jr., wrote that the organization is often pressured to take a stand, by calling out Trump, or condemning “woke” culture, for example. “Yet the moment we do so as an organization is the moment we become a mere faction,” he wrote. “It is the moment we cease to lead a movement for all of America.”

Maybe they have it right. After all, Braver Angels is the only organization I have found across the constellation of bridge-building entities that consistently features a strong chorus of conservative voices to balance the more liberal ones that tend to reign in this space. They appear to me to be truly bipartisan, a feat that may indeed require unwavering devotion to the rule of impartiality. It strikes me that Braver Angels has made the right move for their organization.

But that doesn’t mean it is the right move for me and my organization, Middle Ground School Solutions. When I wrote my book, Learning to Depolarize, I learned a lot about social psychology. Much of our behavior today has its roots in antiquity. For reasons that were once entirely sensible, we cling to those within our tribe and generally mistrust the “others.” We naturally fall into a binary mindset in which we perceive safety and acceptance on one side, and danger beyond. I wonder if, in critiquing President Trump for rhetoric and actions that almost all Americans agree is beyond the pale, we might complicate that human tendency to slice the world in two.

There is broad agreement across party lines about the importance of democratic norms. According to the Polarization Research Lab, whose research is updated weekly, about 85% of both Democrats and Republicans would support the decisions of judges who were appointed by a member of the opposing political party. Other researchers affirm a shared reverence for democracy, with one team summarizing, “Our results show that Americans of all political stripes overwhelmingly endorse democratic norms and reject the use of political violence.” Respect for the democratic underpinnings of society is not partisan—this is not to say merely that it should not be partisan. Rather, research tells us that in fact it is not partisan. Perhaps calling out Trump’s antidemocratic behavior could surface an area of common concern that transcends tribalism.

If Trump were to make good on his infamous boast that he could shoot someone in the middle of Fifth Avenue without losing support, those of us in the bridging space would not hem and haw about whether to condemn the act. Common sense tells us that there are limits to impartiality, even when one’s mission is to bridge political divides. It shouldn’t really be all that hard to determine that we are past those limits. Some of Trump’s words and actions have run afoul of a common sense of decency and democratic decorum and land squarely within the range of “stuff that Americans can agree is not OK for the president to do and say.”

I suggest that we bridgers not shy away from acknowledging this. I sincerely believe that, in so doing, we can model a more nuanced, empathetic way of discussing Trump, one that affirms common American values while frowning upon presidential rhetoric and action that cuts against those values. We can do this. We can call out aspects of what Trump says and does while still holding space for the vast array of presidential action that lies beyond these words and deeds. We can show support for, and ourselves be supporters of, the president without having to implicitly support all that he says and does.

Many of us prescribe intellectual humility as an element of effective bridge-building, and I will exercise a bit of it here. Maybe I wrong to think that calling out aspects of Trump’s behavior will engender agreement across party line. And maybe it’s not even necessary. If I were in the classroom, I would not have to tell students that Trump’s refusal to rule out another term is unconstitutional. Instead, I would help them learn the historical content that would position them to arrive at this conclusion themselves. Maybe in facilitating exchanges across the political divide, the bridge-building movement is facilitating the conditions necessary for people to come to a common understanding that requires no pronouncements. In other words, maybe we can skip the moralizing.

Still, I can’t help but believe there is a place for statements of fact. In engaging with each other, we leave space for passionate disagreement even as we recognize certain truths: we will listen to each other, because we agree on this condition as a prerequisite for building productive community. We agree, too, on the rule of law and on the greater, shared compacts that anchor a wider American community, such as the constitution. That agreement makes it worth critiquing President Trump.

The real problem? YouTube, not Charlie Kirk

For most people, engaging with Charlie Kirk through social media represents just one stop in a journey toward ever more extreme content, with the social media platform’s AI-fueled algorithms serving as conductors. Charlie Kirk does not trouble me. But the experience of engaging with him online feels deeply worrisome.

I’ve been hearing about this guy, Charlie Kirk.

Over the past couple of years, I have read about him many times. I’ve never taken the time or had enough interest to research him properly, but I’ve become aware that he is a consequential young Christian conservative, instrumental in turning out the vote for Trump. I understand that he has a robust social media following and that he frequents college campuses, where he invites any and all comers who wish to spar. He has sounded pretty arrogant to me. Until last week, I had never actually heard him speak, nor had I read anything he’s written. My knowledge of him has been purely second-hand.

I got more interested in this guy when I realized my own children have seen more of him than I have. They live part of their lives online, keeping company with, I now realize, people like Charlie Kirk (“Oh, he’s the bomb,” said my sixteen-year-old).

So I was interested to hear of the stir that had been caused when California Governor Gavin Newsom launched a controversial podcast on which he interviewed Charlie Kirk. I listened to it. To my ear, Gavin Newsom came across as a bit less appealing—a little too glib-- than I expected (as with Kirk, even though I had heard plenty about Governor Newsom, I had never actually listened to him, myself), and I did not find Charlie Kirk to be nearly as objectionable as I expected him to be. Yes, he did seem pretty full of himself, but he was an impressive speaker, incredibly knowledgeable about a range of subjects, and pretty polite. I could see why my teenage boys—and, according to them, many of their friends—find him appealing.

This, then, got me interested in finding out more about Kirk’s reach online. So I dialed him up on YouTube. The first video I watched seemed pretty innocuous. As I’d found while listening to the podcast, Mr. Kirk came across as knowledgeable— particularly about the Bible— and less antagonizing than he’d been portrayed.

The video thumbnail was wildly misleading; the student simply asked one good-faith question with which Kirk gladly engaged. But I soon realized that incendiary labels— regardless of the content of the video— are the hook that fuels YouTube’s engagement.

I recently finished Max Fisher’s outstanding book, The Chaos Machine, which laid bare the machinery of social media: Each click, each engagement, trends towards a more extreme or provocative interaction for the user. It’s how the tech giants retain our attention— and consequently, make money. Intellectually, I know this to be true, but since I avoid social media I have little experience falling down these rabbit holes. So, I gave up some of my afternoon and followed YouTube’s lead, clicking a new thumbnail from the menu presented each time I watched a video.

It only took one click to get to some of the most incendiary content dividing college campuses.

On the heals of this student whom Kirk had DUMFOUNDED, another click brought a lawyer who SILENCED Muslims, before the next video promised content so shocking that it caused a woman to nearly pass OUT. Having begun with Charlie Kirk’s conversation with a college student about Trump’s sexual assault trial, I was now into videos debunking the myth that Palestine is a legitimate place.

By now, if I’m being honest, the thumbnail descriptions started to make me feel queasy. I felt bombarded by ill will.

After just a few clicks, it felt as if the entire world was oriented around an existential struggle to crush, to destroy, and to humiliate.

I also caught on to the fact that much of the content being served up by YouTube’s algorithm was redundant— people had simply captured the same video and reposted it to ride the coattails of outrage en route to securing tens or hundreds of thousands of views for themselves.

After a few rounds of this, I was worn out. My mood was shot. Congress ERUPTS As Ted Cruz HUMILIATES Transgender Activist To Her Face. Ricky Gervais DESTROYS Woke Culture. Kash Patel DESTROYS Cory Booker With This One Response. I called it a day, with the words of technology expert, Max Streusel, ringing in my ears: you’re never extreme enough for the internet.

So Charlie Kirk: The human being, Charlie Kirk, stripped from the headlines of his videos, strikes me as an impressive guy, one with whom I would have many disagreements but whose intellect, faith, and drive I tentatively respect. But it’s hard to extend much grace toward a person who is so nakedly leveraging the dark algorithmic arts for personal profit and notoriety. This content is overwhelming, corrosive, and to my eye dangerous. I think my lesson from this little research project is that Kirk himself is not the extremist I imagined him to be. When he is mixed into YouTube’s algorithm, though, and leveraged to ratchet up users’ outrage, the recipe feels far more dangerous.

In his book, Fisher shares a metaphor that has stuck with me. Researchers have discovered that, although one might imagine the vast array of YouTube’s videos to be something like a cloud, in fact it is more like a subway map, with a user shuttled from one set of videos to another, a predictable pathway carved out by the algorithm. For most people, engaging with Charlie Kirk through social media represents just one stop in a journey toward ever more extreme content, with the social media platform’s AI-fueled algorithms serving as conductors. Charlie Kirk does not trouble me. But the experience of engaging with him online feels deeply worrisome.

Dear Canada: I’m Sorry.

When I was ten years old, Canada briefly became home. I moved in with a family friend outside of Toronto, where for two months I attended school and sang the Canadian national anthem in English and French. I discovered hockey trading cards, which could be flicked by using the thumb and forefinger to grab the corner or, as most of the cooler kids seemed to do, launching them between forefinger and middle finger. I was lousy at both techniques. It was a fragile time in my life, with my mother having died a couple of years earlier and my father eyeing a transatlantic sailing adventure and time to heal. Our friend Kathy—and Canada—welcomed me.

Canada deserves an apology. It won’t get one from Donald Trump, so I’ll do it myself.

When I was ten years old, Canada briefly became home. I moved in with a family friend outside of Toronto, where for two months I attended school and sang the Canadian national anthem in English and French. I discovered hockey trading cards, which could be flicked by using the thumb and forefinger to grab the corner or, as most of the cooler kids seemed to do, launching them between forefinger and middle finger. I was lousy at both techniques. It was a fragile time in my life, with my mother having died a couple of years earlier and my father eyeing a transatlantic sailing adventure and time to heal. Our friend Kathy—and Canada—welcomed me.

I therefore take Trump’s deeply disrespectful rhetoric as both an affront to the country that sheltered me and a betrayal of my own. My instinct is to say that Trump does not speak for me, yet that would be disingenuous. He was elected—again—and while I certainly did not vote for him, I accept that, collectively, we Americans gave him the microphone he wields like a machete.

I have not followed Canadian news outlets, but my hunch is that Trump’s bullying has stirred Canadian patriotism and rallied Canadians in common defense against the threats coming from south of the border. We Americans felt something similar after the attacks of September 11. That week I went out to buy an American flag, but the shelves were bare; the flags had been cleared out by my neighbors, who were feeling similarly stirred. I wouldn’t be surprised if there were a few more Maple Leaves in your parts these days.

In researching my book, Learning to Depolarize, I learned how deeply programmed we humans are to seek the safety of our tribe and guard against danger from beyond. We fall naturally, evolutionarily, into a tendency to divide the world into us and them. Donald Trump has always shown a facility for leveraging this phenomenon to his advantage, issuing a ceaseless stream of warnings about DEI, “wokeism,” immigrants, a shadowy deep state, tyrannical elites in academia or the sciences. The common theme: that “we” are in peril, that “they” are at the gates.

This tactic has had the intended effect on many of us Americans, with a fearful majority of the electorate swallowing their misgivings and ceding power to the authority whom they believe will keep them safe and assure their prosperity. Some are nakedly racist, or xenophobic, but in my work over the past few years I have come to understand that most are not. They are humans, their motivations—like all of us—defying simplistic categorization. Their support of Donald Trump does not disqualify them from earning my empathy, my curiosity, or my respect.

As I apologize for the demeaning stance of our president, I want you to know we’re hard at work down here. I don’t just mean the usual political resistance to Trump—the Democratic congressional delegation from my home state, Massachusetts, for example, which will reliably oppose Trump’s agenda and condemn his personal affronts. I mean also those of us who are leaning into the challenge of communicating and collaborating across the political divide. Having been a classroom teacher for twenty years, this is what I now do—arm students with the skills and dispositions to help them ease political polarization. And there are hundreds of other organizations doing similar work across all sectors of American society, many of which have joined the Listen First Coalition.

I am mortified by what our president has said, and I apologize. As an engaged member of this representative democracy, I accept responsibility for his words. That responsibility includes not just expressions of outrage, which are largely performative, but the real work of reconciliation among American citizens. Trump draws power from the cleaving of American society, and many of us are trying hard to stitch us back together, to muster genuine curiosity about and empathy toward those with whom we disagree. Division fuels Trump and excuses his words and actions. We are trying so hard to ease that divide.

We’re sorry. Please don’t give up on us.

Talking about DEI in the Age of Trump

My hope would be that, as difficult as Trump has made it for any of us to enter into good-faith conversations about topics that he blithely leverages to accrue power, we rise to the challenge. The issue of diversity, equity and inclusion is surely just one of many such topics.

Last week, when Donald Trump suggested DEI initiatives may have led to a plane crash, I was at first disoriented. The claim was nonsensical, difficult to parse, as if a mechanic had blamed cheese for my car’s worn tire. When I got my bearings, though, I recognized Trump’s comment as another battle cry in a years-long effort to conjure an enemy whose defeat requires the unwavering leadership of one great man. An insidious enemy of that sort deserves constant vigilance and, should our attention wander, renewed focus: planes are now crashing down, people.

I traced the origin story of Trump’s war on critical race theory in my book, Learning to Depolarize (starting on page 103). Basically, an anti-CRT zealot brought the topic to Trump’s attention, who then leveraged the intrinsic human fear of the “outsider” to rally a defense against contagion. Over time, the name of the feared virus has morphed from CRT to DEI, setting the stage for the current landscape, in which President Trump has surrounded himself with officials such as Defense Secretary Hegseth who have locked and loaded in preparation for the DEI battle.

I suspect many of Trump’s supporters, having been fed years of corrosive messaging, genuinely believe that DEI initiatives represent repressive attacks against a liberal democracy and that opposition therefore amounts to a defense of our republic. I do not extend this charity to Donald Trump, whose circle of concern appears to reach no farther than himself.

Others undoubtedly share my skepticism of Trump’s motives, which might make it hard for them to take seriously those who, independent of Donald Trump and his hyperbolic, self-serving crusade against DEI, also happen to have critiques and questions about the state of diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives in schools. And yet I think we should take them seriously. Not because I necessarily agree, but because this is part of the democratic ideal that many of us feel is threatened by Donald Trump.

This is what we ask of our students, and this is what is required of us in a pluralistic society—that we resist Trump’s facile tribalism and instead lean into complexity. I write this piece to celebrate and encourage measured dialogue among well-intentioned people about a fraught topic that has been swallowed by Trump’s messaging. Donald Trump opposes DEI to bolster his power. Others question aspects of the work because they want their students and children to thrive in a pluralistic world, and they aren’t entirely convinced that DEI is leading them there.

I’ve heard this in various ways over the past couple of years. The parent of a child at an all-girls school, who I suspect would not vote for Donald Trump if he were the last candidate on Earth, told me her daughter’s school had scrubbed all references to “girls” and “women” from their messaging. As a proud feminist, this troubled her. Would her daughter ever internalize the ideal of female empowerment that had nourished her own life? She brought her concerns to the school’s DEI office but was met with, in her view, a defensiveness that left no room for dialogue.

Ian Rowe, who ran charter schools in the South Bronx for a decade, now serves as Senior Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. As a parent, Mr. Rowe was troubled by what he viewed as a flawed equity audit administered by his children’s school. He became further concerned by the lack of opposition among parents, an experience he discussed in this presentation. As I wrote in my book (page 116), “Rowe’s Parents Unite presentation is thoughtful and measured, and it serves as a reminder to educators committed to DEI work that there is reasonable opposition to the way this work is being implemented in some school districts, aside from the tribal panic that animates many of its opponents.”

Jewish students enduring anti-Semitism have called upon school leaders to reconsider their approach to DEI work. Principled foundations have sprung from the soil of frustration over the state of DEI work in schools. Sanje Ratnavale, whose writing reveals him to be a first-rate scholar of curriculum and schooling, has penned a book called Meaning Loss: Reimagining DEI & Purpose. It seems to me there are an awful lot of thoughtful, knowledgeable people who question whether DEI work is as effective as it could be.

I do not happen to be one of those people, even if I am open to their insights. I have led sessions on white privilege, and I think many of us could stand to learn more about it. I gently pushed for affinity groups at my previous school, and I feel strongly that students of color there would benefit from more of those opportunities, not fewer. My own teenage children have not yet developed the cultural awareness my wife and I would hope for them. So, in general, I tend to lean toward more DEI emphasis, not less.

Still, I haven’t yet read Sanje’s book, and I have little exposure to the work of others who may also have well founded, carefully researched thoughts on the matter. I am not interested in Donald Trump’s fearmongering, but I am intellectually humble enough to welcome well-intentioned and well-informed viewpoints that challenge my own.

I come at this conversation from a background in political polarization. The divisions of our times increasingly drive us toward the security of those whom we consider to be our political in-group while stoking mistrust of those across the divide. It would be easy, and entirely understandable, for supporters of DEI work to assume that opposition to or questioning of that work springs only from the well of mistrust that Donald Trump has dug.

My hope would be that, as difficult as Trump has made it for any of us to enter into good-faith conversations about topics that he blithely leverages to accrue power, we rise to the challenge. The issue of diversity, equity and inclusion is surely just one of many such topics. Folks in my circle wonder what resistance to the second Trump administration looks like these days. For me, it looks like summoning the courage to carry on with good-faith discourse about contentious topics, in defiance of Trump’s incessant attempts to cleave the country in two, so that we may model that habit for our students and children.

The Curious Case of the Media Literacy Haters

I had plenty of satisfied customers when I taught middle school. A few weren’t so happy, including one or two who fell asleep in class and a parent who once berated me so lustily that a colleague down the hall wondered if someone had been hurt (I guess I had been, a little bit). Mostly, though, things went smoothly. The terrain felt unfamiliar, then, when over the past year I found myself the focus of deep distrust and vehement online condemnation.

I had plenty of satisfied customers when I taught middle school. A few weren’t so happy, including one or two who fell asleep in class and a parent who once berated me so lustily that a colleague down the hall wondered if someone had been hurt (I guess I had been, a little bit). Mostly, though, things went smoothly. The terrain felt unfamiliar, then, when over the past year I found myself the focus of deep distrust and vehement online condemnation.

Courageous Professional Development— and Backlash

In the fall of 2023, I helped lead educators in a months-long professional development opportunity under the auspices of Courageous Rhode Island. The end goal was for teachers to design learning opportunities that would position their students to "reduce the fear and hate that leads to violence." After one participant posted an insider's "expose" of the experience, online comments decried this government-sponsored brainwashing of American children (the program was supported by the Department of Homeland Security).

Readers characterized me and my colleagues as inept (“The people pushing this stuff are not competent in any traditional education field”), traitorous (“terrifyingly un-American”), and downright repulsive. “Way to ruin my Monday morning,” wrote one queasy reader. “Now I am going to have a sick taste in my mouth all day thinking about the innocent children who cannot get out of the schools.” That the post eliciting these reactions was wildly, extravagantly inaccurate is now beside the point; what interest me are the concerns it surfaced.

Most of the comments adhered to a couple of common themes—that the federal government overreaches and that media literacy programming extinguishes original thought in favor of woke indoctrination. “Chinese-style cultural Red Guard comes to America,” wrote one disgusted reader.

The great, shining irony is that these detractors, in bemoaning state-imposed thought control, appear blind to the inherent goal of media literacy to strengthen the skills of discernment and critique. During our final meeting of the professional development series, the participant who later penned her expose said that, in her view, media literacy education has no place in K-12 education. Current events, she asserted, should never be introduced into the classroom, because the media used to deliver the news is inaccurate (she cited MSN as an example).

And this is the point in the story where I wonder—without any tongue in cheek—aren’t we all sort of after the same thing?

Isn’t everyone in this tale—those of us who delivered the programming, and the mole who unearthed our villainy, and those who commented on the newly unearthed villainy—hoping to equip kids to think for themselves? A proponent of media literacy education would suggest that exposing kids to MSN, or any other source of news, helps them interrogate that media by asking about authorship and purpose and the techniques used to hold the reader or viewer’s attention (see the Media Education Lab’s five key questions of media literacy). While some may fear the effect of exposing children to biased media, proponents of media literacy maintain that it is this exposure—and the practice of then critiquing that media—that positions students to think critically and sniff out bias.

What a frustration to read comment after comment decrying the erosion of independent thought, when those readers were targeting the very programming that, at its core, bolsters such critical thinking. The folks lobbing spitballs at me were the same people who, theoretically, in a less polarized world, one would expect to be the most vocal proponents of the programming they were decrying. So why the profound disconnect between these two camps—those of us delivering the workshop and those eyeing it with suspicion—and what could be done to bridge the gap?

Language as Wedge or Bridge

I tossed out that question to colleagues among the Listen First Coalition last spring and joined several for a discussion. They offered wise counsel: solicit testimonials from former attendees or convene a bipartisan lineup of outside authorities to speak on behalf of media literacy; consider how language can unintentionally provoke in these polarized times; acknowledge the volatility of language when convening a new cohort of learners, and communicate what we mean when we use certain terms.

Respectful of the power of rhetoric to engage or repel, I looked back at the language used by Courageous Rhode Island to advertise its mission—that is, the wording guiding our professional development program. It reads: “Courageous RI, with support from the Department of Homeland Security, works to prevent rising violence and extremism in Rhode Island with authentic and respectful conversation.” This is the vision that originally hooked me, a goal that was well worth my time and talent. But it may have had the opposite effect on those across the political aisle.

Several organizations have recently studied the divisive nature of language, including Braver Angels, who considers “extremism” to be among the very most polarizing words, “likely to alienate a vast number of Americans.” In centering that word, had we in fact antagonized a segment of the population before we even began? “Disinformation” is similarly slippery, evoking censorship among many conservatives. “Speech crimes and censorship have become the norm in the West,” wrote Jonathan Turley on Fox News recently. “A new industry of ‘disinformation’ experts has commoditized censorship, making millions in the targeting and silencing of others.” Glancing back at our promotional language, it would appear that I and my colleagues are perceived to be those experts. “By joining Courageous RI,” read the invitation to apply, “you become part of a vibrant network of educators and librarians who share a common goal: combating disinformation and promoting media literacy and active listening.”

Should it really have been a surprise, then, given the divisive nature of the wording used to describe some of the most critical objectives of our programming, that one reader summarized our plot as, “Red Guard disinformation charade permeates kindergarten class?” Although our intent was to solicit participants of varied political stripes, and although we took pains throughout the program to support those across the political spectrum, the impact of some of our foundational language may have been to repel. I spent twenty years in classrooms, speaking with children about the balancing act of intent and impact. Now I wonder whether the impact of some of our language was to undermine our noble intent.

In Pursuit of Bridge-Building Language

If so, what to do about it? Might there be ways to promote the important work of media literacy education without unintentionally antagonizing? I think back to a jarring conversation I once had with a woman whom I knew to be concerned about racial intolerance, yet who disoriented me by characterizing the term “anti-racist” as “evil.” I eventually came to see that she understood the term as an attack against people, rather than ideology. I had known the word as a condemnation of racism, while she understood it to denounce other human beings. To her, “anti-racist” was an expression of hatred.

It strikes me that something similar may have been at play regarding my experience with this professional development program. I signed on to combat extremism, but some understood that fighting stance as an expression of contempt for conservatives. I set out to help students deflect disinformation, and it sounded to some like shielding them from the full spectrum of truth. I aimed to strengthen our democracy, and as far-fetched as it seems to me, some perceived attack.

Maybe we should take a page out of the Prohuman Foundation’s playbook, an organization whose name suggests working toward rather than against something. If we were to do the whole thing over again, could we tweak our messaging to ease the perception of attack and enhance a feeling of collaboration?

PACE recently completed its Civic Language Perceptions Project, which, like Braver Angels, identified terms that land differently on either side of the political aisle. It also identified words that have generally positive connotations, regardless of political orientation, such as “community,” “service,” “belonging,” and “liberty.” Could a tweak to the programming we offered be to focus on what we want of students, rather than what we fight against? Instead of “combating disinformation,” for example, could we employ what PACE calls “bridge-y” language and say we strive to “build a shared community of learners who investigate the origins of their beliefs?” Too wordy? I have faith that a small group of committed media literacy practitioners could huddle up and craft something better.

Some will roll their eyes at the futility of wordsmithing. I get it. But we cannot pretend that political divisiveness is not at play here. We cannot imagine that it is enough to deliver enlightened programming when that programming is perceived as an assault by those who, if we’re being honest, may be in most need of it—at least if we are serious, as I certainly am, about sharpening students’ media literacy skills and helping them curate information in a way that promotes democratic stability. If we are, I think it’s worth further conversation and contemplation about how to help folks across the political spectrum realize these goals.

Closing Thoughts

I am not suggesting the goals of our professional development offering were misplaced. My commitment is unwavering. In suggesting that we find ways to describe our work that avoid triggering words like “extremism” or “disinformation,” I do not presume that the problems these words describe are any less dire. I just suspect that there is room to find some overlap of shared purpose across lines of political divide if we are open to introspection and self-assessment.

In my book, Learning to Depolarize, I laid out the origins of the Trump-supported campaign against what he called critical race theory in schools. As I suspected would happen, those most aligned with Trump then turned their attention to other aspects of schooling. Race was a weapon of wokeness, and then gender, which bled into SEL, and now media literacy—all are met with derision among those looking for evidence of the liberal attack. I guess that’s some cold comfort—in receiving backlash for this particular media literacy programming, I am among the good company of educators delivering all sorts of learning opportunities that deeply benefit students and yet that are in the political crosshairs.

I could—we all could—bemoan the errant ways of those who post comments critical of our work and take solace instead in our achievements (which would not be hard—see this page of the Courageous RI website for links to the dozens of projects completed by our PD participants). But it doesn’t do anyone any good to mount our high horses and ride righteously away from the detractors.

The Media Education Lab’s fourth key question of media literacy reads, “How might different people interpret the message?” Let’s not be afraid to apply that question to our own work.

The Day After: Teaching After the Election

This is a generalization. Some students are indeed captivated by this political season, or terrified of it. Some, by virtue of their personal circumstances, may feel that the results of the election could imperil their families or threaten their most cherished values. But lots of kids are not really that focused on politics. The cautionary signal I read, then, is that we should move gently as we plan for the day after, careful not to assume an acute need among a preponderance of students to parse election results or interrupt school routines; “the day after” may in fact call for normalcy.

Last week, en route to a school in Washington, DC, I nipped into a few of the Smithsonian museums. I saw a Rembrandt and a Monet. In a dimly-lit section of the American History Museum, I gazed upon the original Stars and Stripes. And in the Air and Space Museum, I unexpectedly stumbled upon a display about the TV special The Day After, a film that vividly portrayed a hypothetical Cold War nuclear exchange. Today, it seems as if it is our own internal divisions threatening to lay waste to American society, and educators wonder what school should look like “the day after” the election.

To answer that question, it seems helpful to think about two distinct constituencies: the kids and the adults. Having visited a dozen or so schools over the past few weeks, I sense a degree of projection on the part of at least some educators. This presidential election is the subject of intense focus for many of us, a source of constant anxiety. Consumed as we are, we may unconsciously assume that others—including students—are equally invested.

Anecdotally, though, it seems that many of them are not. I’ve had several teachers at schools in various states tell me that, to their surprise, these students are more disconnected from the election than students in previous election cycles, that they have less interest in this horse race than the adults, certainly, but also less interest than those who sat in their seats four or eight or twenty years ago. I have yet to encounter a teacher who has said the opposite—that their students are uncommonly engaged by the election.

This is a generalization. Some students are indeed captivated by this political season, or terrified of it. Some, by virtue of their personal circumstances, may feel that the results of the election could imperil their families or threaten their most cherished values. But lots of kids are not really that focused on politics. The cautionary signal I read, then, is that we should move gently as we plan for the day after, careful not to assume an acute need among a preponderance of students to parse election results or interrupt school routines; “the day after” may in fact call for normalcy.

Where there is a curricular connection, teachers will want to make the most of the election, leveraging it not only in the obvious domains such as social studies, but anywhere else the election could enhance learning (think electoral math or the art generated by protest, etc.). So for some educators, the day after (or weeks after) will provide a teachable moment to make an organic curricular connection.

Beyond those curricular touch points, schools may want to carve out some containers for students who would benefit from further processing. As is the case with traumatic events generally, some students will come to school feeling wounded or lost in the wake of the election (while others, of course, may feel jubilant and righteous). We want to be sure to open ourselves to those who will need extra support, which we might do by asking kids to give us an emotional “fist to five” in an advisory period (see page 32 of this Learning for Justice guide) or other community gathering. I could imagine an optional meeting at lunch or some co-curricular block, as well, that would provide a space for those who are interested.

In general, then, I suggest a “business at least somewhat as usual” approach to school following the election. We cannot lose sight of the fact, though, that some students will need us more than others, and we must find ways to identify those students and then create the time and space to follow up with them individually or in small groups.

Some schools may also want to seize the moment by building in an antidote to the madness of the coming weeks. Messages and modeling of unity, conciliation, curiosity, and empathy could be just the thing to soften the rhetoric of division and worry that is sure to prevail in most media circles. See this page of my website for several options, or take a peek at this new 90-second video. Let’s remember, though, that there’s not necessarily any hurry—I’m not sure the time following the election is that much more ripe for this sort of teaching than, say, the rest of the school year. The election will come and go. The need to prepare students to reach across lines of divide and disagreement will remain.

But all of that still leaves the adults. We are the fragile ones.

It would be helpful if school leaders could articulate for teachers what it would mean to show up as a “professional” the day (or week) after the election. I have been reminded over and over recently of the number of schools in which one or more teachers came to work after the 2016 election emotionally distraught and unable to, in the eyes of their colleagues, be the grown-ups their students needed. Schools expect their teachers to hold it together this time around, regardless of the outcome. What does that mean, though? I personally believe that it can be instructive for students to see at least some of their teachers model healthy emotional responses in times of need—to hear an adult say, for example, “I’m having sort of a rough day, but I’ve been sad before. I know I’ll get through this day, too.” People will have different views about the question of what professionalism looks like the day after. It would be helpful to clarify.

Beyond the façade we show our students, it is reasonable to predict that teachers may broadly need some support in the wake of the election. It is plausible that we may enter a period of uncertainty regarding the electoral outcome, and that this uncertainty will breed anxiety. School leaders may want to see this handful of hypothetical election outcomes created by the TRUST Network and the Bridging Movement Alignment Council in order to imagine what may lie ahead.

I know that some schools will have extra counseling resources on hand after the election. But we can help ourselves, as well, by tending to our media hygiene in the days and weeks after the election. In order to pay the bills, news outlets require attention, and attention is most easily commanded by serving up incendiary content that triggers strong emotional responses (I recently learned the term “rage bait” from a student). Let’s limit our news consumption to a reasonable amount as we ride the roller coaster of emotions following the election, and perhaps some may want to try less sensational, more even-handed sources of news, such as Tangle or 1440. On election night, Braver Angels is holding an online meeting to bring together Americans across the political divide for conversation and community, kicking off a week of similar events; I could imagine many educators would benefit from a gathering of this nature.

Yes, it’s true. The day (or week, or month) after is coming. Let’s see it as yet another chance to do some good teaching.

Tips for Teaching the 2024 Presidential Election, Part Two: In the Classroom

How do we teach the 2024 presidential election? Consider these classroom tips to tame the divisiveness of the election and help students reach across lines of divide and disagreement.

#1: Make a community agreement (posted 1/29/24)

For anyone who has seen me present, this is old news. But for everyone else, I urge you to craft a set of durable, visible, thought-provoking norms that will help students understand how they are supposed to engage with each other. The election might get slippery. Communities need guardrails. These are the guardrails.

Many teachers have some version of such an agreement, although they tend to get neglected (see: dusty, faded poster you once triumphantly laminated but which you now only notice when the thumb tacks get knocked off). It’s time to get back to that agreement, to revise it if necessary, or to craft a new one. Facing History has a helpful lesson on co-creating such an agreement (which they call “contracting”) with students.

For my money, a useful community agreement (or contract, or set of norms, or whatever you want to call it) will probably include two sort of different, but complementary, sets of commitments. One is about behavior, such as, “We agree to…

Listen to learn, rather than to refute

Avoid interrupting

Ask follow-up questions

The other set of commitments is more about mindset—it’s about cultivating a way of thinking that will in turn drive classroom behavior. This could include statements such as, “We agree…”

that listening does not necessarily indicate endorsing or agreeing

that we are enhanced, rather than diminished, by being around ideas with which we disagree (with thanks to Simon Greer, whose Bridging the Gap initiative is now managed by Interfaith America)

to take winning off the table (with thanks to the Better Arguments Project for that language)

Those are meaty statements, and not all teachers may agree with them. Think carefully about what you are trying to teach, though, and be sure that the rules of your road—in a classroom or the broader learning community—guide students toward the goals you value. Get your agreement in order, and then feature it relentlessly. If you make it matter—if students see that you mean what you say—it will provide the stability and clarity you’ll need when the divisiveness of the election starts to feel oppressive.

#2: Look for the helpers (posted 2/1/24)

Our political leaders can be terrible role models (some, yes, are really, especially terrible). It is therefore understandable that teachers might hesitate to attend to the election because doing so—featuring this nasty rhetoric—feels like more of a disservice than a service to our students.

But we can show our students examples of elected officials who are in fact playing nicely. The joint campaign ad of the 2020 Democratic and Republican candidates for governor of Utah is one example. Spencer Cox won that election and, as the current Chair of the National Governors Association, has launched a Disagree Better initiative that features video snippets of governors of opposing political viewpoints engaging in civil discourse.